Bikefast has obtained data from the Department for Infrastructure (DfI) which shows a widespread and enduring culture of creating urban cycling routes on ‘shared’ pedestrian footways – against its own policy guidance, strong advice from disability groups and the expectations set by the Northern Ireland Bicycle Strategy.

Several announcements of shared footway “upgrades” in 2020/21 prompted Bikefast to work with MLAs Andrew Muir and Philip McGuigan to source data from DfI through a series of NI Assembly Questions. This sought to detail the cycle routes delivered by DfI Roads Divisions engineers in each of the five years from 2016/17 to 2020/21, by the three primary types listed under DfI’s existing policy guidance:

- totally separate facility

- cycle lane in the carriageway

- shared walking/cycling facility

That guidance document, Measures to regulate traffic, Road Service Policy and Procedure Guidance (RSPPG) E063 , which was first issued in November 2011 (and apparently not revised since) contains the following section on cycling measures:

2.2.12 Cycle Routes – these orders designate facilities for use by cycles only, and can also cover combined pedestrian/cycle facilities.

2.2.12.1 A cycle route that is solely on the carriageway is referred to as a cycle lane, and any route that is off, but still close to, the carriageway is referred to as a cycle track.

2.2.12.2 The general approach to the location of cycle routes is that a totally separate facility should be considered first. However, limited space between the existing road boundaries may restrict this possibility. If a totally separate facility is not practical then the possibility of a cycle lane on the carriageway should be assessed. The speed and volume of traffic needs to be considered. Outside of a 30mph speed limit a cycle lane becomes less attractive to potential users, with vehicles and in particular larger ones travelling at higher speeds increasing any sense of unease. Shared walking/cycling facilities should ideally only be considered when the previous two options have been discounted. Where space permits a segregated facility should be provided with the cycle route and footway separated using a continuous solid white line.

There is an obvious hierarchy of provision here, with shared facilities detailed as a last resort. This has been more forcefully clarified in new cycle infrastructure design guidance Local Transport Note (LTN) 1/20, adopted in NI in July 2020, which states in Summary Principle 2:

“Cycles must be treated as vehicles and not as pedestrians. On urban streets, cyclists must be physically separated from pedestrians and should not share space with pedestrians. Where cycle routes cross pavements, a physically segregated track should always be provided. At crossings and junctions, cyclists should not share the space used by pedestrians but should be provided with a separate parallel route.

“Shared use routes in streets with high pedestrian or cyclist flows should not be used. Instead, in these sorts of spaces distinct tracks for cyclists should be made, using sloping, pedestrian-friendly kerbs and/or different surfacing.”

But the data we’ve obtained shows that shared walking/cycling facilities have been, and continue to be, the primary choice for DfI engineers in urban settings across the country.

What the data shows

In the last five years, 60 cycling route schemes have been progressed as part of road improvement / resurfacing schemes in Northern Ireland. 44 of these were shared walking/cycling facilities, a stunning 73% of the total.

Just nine schemes (15%) were in the highest quality category of totally separate facility, and four of those are temporary “pop-up” cycleways which can be withdrawn after a set period. No separate schemes were delivered outside Belfast (8) or Derry (1).

No cycle lanes on the carriageway (painted advisory / mandatory lanes) were progressed in the last five years anywhere in Northern Ireland.

92% of all new cycling routes were in urban settings, with just five schemes in rural settings – although three of these were on the same road delivered in separate phases (Foreglen Road, Dungiven).

Interactive maps are only usable in Google Data Studio (click here)

Just 26km of cycle routes were delivered in Northern Ireland over this five year period, little more than 5km per year.

These were the first full (financial) years since the launch of the Bicycle Strategy for Northern Ireland in late 2015. That document promised “careful planning, high quality infrastructure and effective behaviour change campaigns” to create “a network of high quality, direct, joined up routes“, but it also contained this key section:

“All road users have an equal right to make their journey, whatever the mode of transport they choose to use. However, it is important to recognise that some categories of road users are more vulnerable than others. For example, those using a bicycle on a shared footway/cycleway can make pedestrians feel more vulnerable, while those driving a motorised vehicle can make those cycling, running or walking feel more vulnerable. This is the logic behind the concept of a hierarchy of road users which has been developed for use in the planning and design processes for new developments and proposed traffic management schemes.”

It’s important to note that (counter to popular understanding) cycling schemes are generally designed and delivered by the four DfI Roads Divisions, rather than the Active Travel Unit, a policy team in place since 2013, or the Walking and Cycling Champion, a post created in May 2020.

What’s the problem with urban shared footways?

Pavements are spaces where pedestrians expect to be separate from faster and larger modes of transport. Cycle facilities are spaces where those cycling expect a level of protection from vehicles and to be separated from the slower, more erratic movements of pedestrians. Shared footways puts these two modes into direct conflict – and with higher degrees of usage in urban settings – usually with no explicit framework of expected behaviours other than ‘careful now’ and ‘sort it out among yourselves’. But the harms are real.

The Inclusive Mobility and Transport Advisory Committee (Imtac) is a DfI-supported body which advises government and others on issues that affect the mobility of older people and disabled people. Imtac released a statement on cycling in 2018 which dealt clearly and firmly with shared footways:

“Both pedestrians and cyclists are made vulnerable by a society and public policy framework that gives priority to motorised traffic over people.

“The Committee firmly believes that cycling should be an inclusive mode of travel, open to all including older people and disabled people.

“In most circumstances Imtac does not support the use of shared footways between cyclists and pedestrians. Shared footways can impact negatively on all users, but has a particular impact on some older people and disabled people by creating an environment where they feel unsafe. More generally this type of infrastructure is likely to create conflict between users and frustrate both cyclists and pedestrians in equal measure.”

Speaking as a blind person, shared footways are a terrible idea for everyone concerned. The amount of times I’ve had nearmisses with cyclists because I was supposedly in the way. I now try and avoid that footway altogether. I’m thinking of the pavement on the Ormeau Road

— Joe Kenny (@joekennymusic) April 26, 2021

Shared footways are also substandard from a cycling point of view for several reasons:

- interaction with pedestrians

- imbalance of speeds and expectations

- street clutter creating obstacles and pinch points

- ever present danger of vehicles

- lack of priority at junctions

Brian Deegan is a Design Engineer at Urban Movement, who spoke in Belfast at the DfI-organised Northern Ireland Changing Gear seminar in 2014. Deegan published a paper for the Institution of Civil Engineers in 2015 which looked at ten years’ worth of cycle infrastructure delivery across the thirty-three boroughs of London from 2001 to 2011. The paper looked at the type of infrastructure delivered, its level of service to the user and whether it led to an increase in cyclists. Deegan found that those boroughs that mainly focused on shared use footways arrested the growth of cycling even when compared to two of the control boroughs who had not delivered anything for cycling. So in conclusion: shared use footways seem to actively discourage cycling.

Sustrans is the sustainable transport charity which works to make it easier for people to walk and cycle. A spokesperson for Sustrans Northern Ireland said:

“Sustrans has been calling for separate protected cycle lanes for many years. Shared pavements often throw pedestrians and people cycling into conflict with each other, so in areas of high footfall this is not good design. The Belfast Bike Life survey, produced jointly by Sustrans and DfI, found that a majority of people – 81% – support building more protected cycle routes, even when this can mean less room for other road traffic. We would like to see government address the imbalance in road space it provides for all users, especially the most vulnerable.”

Bikefast took a quick sounding on social media and several people put across strong views on how shared footways affect their daily experience, even becoming a barrier to mobility.

Share the space means share the pace, so they have very limited utility for those on bikes and can be frustrating for those on foot. I spend the entire time on my bike apologising for my existence and on my feet looking over my shoulder for the next bloody bike.

— Mícheál Mac Grianna (@mgreene754) April 26, 2021

Negative experience of shared paths is overwhelming. They’d work if there were common rules and courtesy that all users adhered to, but everyone assumes they’re in the right all the time. Conflict and antagonism are too common. https://t.co/GTrlgpUPZv

— Dave Leathem (@dave_leathem_uh) April 26, 2021

Many more responses are collected at the end of this article.

How many shared footways are there in Northern Ireland?

As far as DfI has indicated in the past, there is no full database of cycling facilities in Northern Ireland. Annual DfI Roads Divisional reports to councils usually trip over themselves to impress with figures for the total road network managed under their remit, but cycling infrastructure? No.

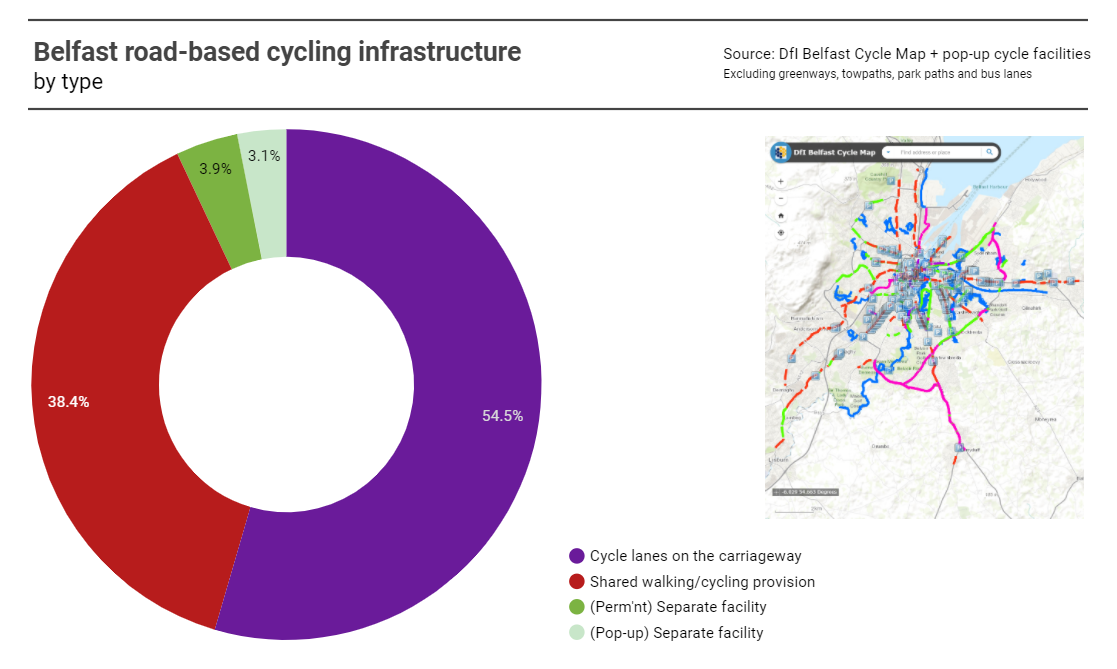

The best we can manage is a snapshot in Belfast where DfI have worked to create a database and map the existing facilities. We took the three categories of road-based and road-adjacent facilities (discounting bus lanes and greenways) as laid out in RSPPG E063.

Cycle lanes on the carriageway (mostly defunct advisory cycle lanes and mandatory cycle lanes, ie paint) dominate in Belfast, covered as they are in parked cars and fairly useless in terms of a track record of encouraging modal shift.

The key point is the almost 37km of shared walking/cycling facilities designated in the city – that doesn’t count off-road paths such as greenways and parks. There are just 3.7km of permanent separate cycling facilities – a ten to one imbalance the wrong way. That will be reduced somewhat if the current pop-up cycle lanes are made permanent, but DfI have pushed cyclists onto pavements in a big way in our biggest urban area.

That lazy culture of favouring shared space has gone so far that a suggestion from Belfast Transport Hub designers (now thankfully dropped) was that the pavements on Great Victoria Street should be converted to shared walking/space. Yes, right here:

A case study among the schemes – O’Neill Road

O’Neill Road was a strange case on paper when it was announced in July 2020. Here was an urban road in Newtownabbey (the outskirts of Belfast) which in its previous layout had a two-way single carriageway arrangement incorporating with-flow advisory cycle lanes and pedestrian footways behind grass strips. Wholly useless for inexperienced / nervous / young people on bicycles, favouring more experienced riders who benefitted from the cycle lane’s priority over side junctions – but the principle of dedicated cycling space separate from pedestrian space was clearly established here.

Previous arrangement on O’Neill Road as seen in 2015

When the new scheme was being considered by engineers, “limited space” was clearly not a deciding factor against a totally separate facility, and cycle lanes on the carriageway were already present. So it was a head scratcher when the scheme announcement proclaimed “enhanced footway/cycleway provision” which would “give benefits to the whole community and help encourage more people to consider walking and cycling journeys”.

New arrangement on O’Neill Road in 2021

As seen from this image, more experienced users simply don’t use footways whether they’re designated as shared or not, primarily because of the inherent danger of the speed differential between themselves and pedestrians, and the otherwise unnecessary need to stop and give way at every left hand junction.

A well designed separate facility – completely possible given the space – would capture many more (but not all) users at the more experienced end, and deliver a better experience for new / inexperienced / nervous users. But look at the new road layout – central hatching to ensure free-flow of traffic when vehicles want to turn right, both traffic flows further apart than before and (in theory) fewer cyclists to worry about, off the carriageway. In the real world, road engineers have lifted average vehicles speeds (steadier flow) and visually encouraged higher individual vehicle speed, all wrapped up in the greenwashing of an “upgrade” for pedestrians and cyclists, which it is anything but.

Yip! I get shouted at sharing a path and saying “excuse me “ on my bike but also get shouted at by cyclists when walking the dogs. “Get out of the way bitches!” last week.

— Michelle Grant (@MichelleGrantBS) July 8, 2020

What are the cultural effects of lots of urban shared footways?

The most insidious aspect of DfI’s concentration on shared facilities is its “gaslighting” effects on the public. The term refers to when a person or wider group is psychologically manipulated into questioning and second-guessing their reality.

There are several layers to DfI’s (unintentional) gaslighting:

- PR activity giving the appearance of active travel progress, while substandard schemes are behind the headlines

- claiming the creation of new routes which are often only “delivered” by the application of paint on a pavement or installing signage

- simultaneously creating a culture of pavement cycling while public awareness campaigns deride the practice and its (clear) ill effects

- forcing active travel advocates to openly criticise the overwhelming majority of DfI’s cycling output

- sowing observable, lasting and harmful division between groups of vulnerable users – when the common source of daily woes is actually DfI

- all the while ensuring maximum traffic progression by not having to sacrifice road space to active travel space

How many times have you seen arguments play out on the street, on social media, even on the airwaves between disgruntled folk coping with the awful street environment delivered by engineers? The pedestrian furious at a near miss from a cyclist on the pavement?

As the roads are quite empty can someone please explain to me why some grownup cyclists are cycling on the pavement? I've nearly been knocked over a couple of times while out walking and taken evasive action by jumping into a hedge. Not a good look.

— Pamela Ballantine (@PamBallantine) April 25, 2020

The cyclist unsure what reaction the sound of a bell will elicit from pedestrians? Drivers angry that cyclists aren’t using the cycle lanes provided for them, when they consider it safer to be on the road. DfI’s muddying of the water on shared footways is directly contributing to this mess – does it really matter to a blind pedestrian whether an engineer has rebadged an existing footway to allow cycling? Does that make it feel any less dangerous?

I don’t feel safe on shared paths, I can’t see cyclists coming towards me & I can’t be sure I’m not veering into their allocated area (if there is a marked area). Plus if I was using my cane I’d prefer to be at the kerb side to use as a guide but that’s where the bikes are.

— Caryn & GD Piper (@CarynYoung19) April 26, 2021

How does pointing to a written policy, demonstrating a risk assessment was carried out, insisting that a scheme meets certain in-house standards, make Caryn feel any happier about trying to move around these facilities? When does empathy and people-centred place-making begin to override road engineers’ worst instincts?

If DfI has made a decision for Northern Ireland to pursue a shared footway strategy, the public should be consulted on it. There hasn’t, of course, been such a decision – and yet the output is shaking out as if this was hard policy. And no-one has been any the wiser or able to challenge it, until now.

What does the future hold?

Better design guidance in LTN 1/20 is in place, but is it actually being used correctly (or at all) by engineers? Recent post-LTN 1/20 urban road improvement schemes have continued to include shared walking/cycling facilities – with serious money being spent on substandard facilities that will now likely be in place for decades:

- O’Neill Road, Newtownabbey (£260,000)

- Ballymacash Road, Lisburn (£165,000)

- Larne Road Link Dual Carriageway, Ballymena (£154,000)

And several future schemes are indicated to have shared walking/cycling facilities integrated:

While well-designed shared facilities in some more rural settings may be appropriate, even then you only need to look at scheme designs around grade separated junctions – take the recently upgraded A26 Frosses Road as an example, and see how engineers think cyclists should manoeuvre around their near-motorway speed pet road projects – to see that route utility is crushed without careful planning and utilising international best practice in terms of cycle route underpasses and bridges.

What is the reaction to the data and findings?

Andrew Muir MLA, who obtained data from DfI Roads Eastern and Southern Divisions, said:

“The information from the department uncovers a clear disconnect between DfI policy and what is actually being delivered on the ground. All of the evidence shows that to encourage cycling, you need to make people feel safe, and segregated cycle lanes are by far the best way to do this. There are examples of successful shared routes which have made use of the OnePath initiative, such as the Comber Greenway. However, it is concerning that shared footways in busy urban areas appears to have been the department’s default in recent years, even when other options are available.

“The figures on the amount of cycling infrastructure that has actually been built in the past five years are shameful. The Minister for Infrastructure recently announced a relaunch of the Belfast Bike Strategy. When this is published, we need to see segregated paths, funding, and timelines to ensure that this vision finally becomes a reality.”

Philip McGuigan MLA, who obtained data from DfI Roads Northern and Western Divisions, said:

“5km of cycling infrastructure per year for the last five years is pretty pathetic. We need a radical change of direction from within DfI when it comes to planning and designing infrastructure, that will allow for citizens the ability to cycle safely.

“No longer is it acceptable that cycling is treated as an add on or an afterthought – it must become central tenant of departmental policy making moving forward. This is particularly the case in urban environments – cities and large towns – where we can easily get people out of their cars and onto bikes if the correct infrastructure is in place. Cycling-only infrastructure is an investment in our health of our population and in our environment.”

In response to the data analysis and the issues it raises, a spokesperson for the Department for Infrastructure said:

“Minister Mallon has made clear that she wants to drive forward a programme of measures to reallocate road space to create more space for cycling and walking. She has established a new £20m capital blue/green infrastructure fund to boost active travel and continues to work with Executive colleagues, councils and other partners to help deliver cleaner, greener, sustainable active travel infrastructure across our island including creating more cycle lanes.

“We clearly need to create more opportunities for active travel and make our roads safer for those who want to cycle and walk and the department recognises that segregation provides the best solution for everyone. While this is not always possible within current constraints, the department under Minister Mallon is committed to bringing about change and will where possible provide fully segregated facilities.”

Comment by Bikefast

It’s harder to think of clearer evidence of a particular practice and culture within an organisation than this. There was a general sense of unease at how cycling was being delivered in recent years, but nothing this stark to point to. Bikefast and others have been calling for reform of DfI structures as the only way to ensure this is fixed, and that Northern Ireland starts to see output from the ambition and vision that the current Minister (and most every other Minister) articulates.

Road engineers have been in control of the Bicycle Strategy since before there was a Bicycle Strategy, and have little interest in doing the hard work to make the highest quality implementation happen. If anyone in DfI disagrees, show me any different. When the head of DfI Roads Eastern Division boldly declared to Belfast councillors in November 2018 that the 2018/19 programme of planned cycle measures was “extensive”, who knew that the only item from that list which would be built two and a half years on would be a 120m shared walking/cycling facility at Broadway roundabout. It hits a little different today.

There are moves afoot to change DfI’s culture from within – to make cycling mainstream, to embed active travel in everything they do, to put walking, wheeling and cycling front and centre. I was sold those same assurances as far back as 2014, and look where we are now. Gentle persuasion is fine, but while that effort is going on, DfI’s top brass needs to clip some ears. Right now, a halt should be called to all urban shared walking/cycling facilities in current design development and future planning. All efforts from this moment need to be put into the highest quality schemes, and that must not mean a reduction in overall output – the climate emergency, regrowing congestion and the need for more active lifestyles requires a serious increase in activity.

There probably needs to be an updated and dedicated RSPPG which focuses solely on active travel schemes, reflecting LTN 1/20’s new reality. And a full audit and mapping of all cycling facilities across the country would allow the public to see what’s there, establish the baseline for growth and opportunities to level-up, help DfI to truly feel ownership of this (seemingly forever nascent) network, and allow advocates and politicians to effectively hold DfI to account for proper, best standard delivery in the future.

There is so much more to unpick from the data:

- the regional imbalance, with so little of quality outside Belfast

- the lack of a ramping-up of delivery during coronavirus, when other places around the world rolled up their sleeves

- the societal conflicts which are being unnecessarily created and stoked by.. a transport department?

- the utter lack of focus and effective stewardship of active travel strategy, and ownership of failing to meet Programme for Government targets

But for me the most critical part of this research is to have heard the experiences of disabled users of these shared urban footways. The only way to make that right is to stop development, design out the existing facilities in favour of best practice segregation as soon as possible, and ensure we make our urban spaces fully welcoming and accessible to everyone. We can be divided by unwanted circumstances, argue and fight over who’s right and wrong at any given point of conflict, or we can unite our voices to make DfI to do better.

Comments from the public

“They’re mostly pretty miserable to use in Belfast – there’s just too many people for them to be viable. They work okay on rural links where foot and cycle traffic are both low (but even then they’d really benefit from having priority at side junctions)” @alexcreid

“I could never use shared spaces. It’s difficult enough to cope with pedestrians on pavements. The ‘walking’ area is barely wide enough for an average size wheelchair. Society hasn’t made pavements comprehensively accessible for wheelchair use. Adding cyclists to the space is 🤯” @spankychair

“Speaking as a person with mobility issues, it appears to me that EVERY footpath is being used by cyclists now, even walkways. Many people have hearing or vision impairment, or move very slowly, and speedy cyclists on pedestrian paths cause difficulties for us” @NoelleRobinson7

“I only use them when I have my kids with me and we’re all travelling quite slowly. Otherwise, I prefer to use the road when I have right of way travelling forwards, as opposed to stopping at every junction to make way for cars.” @clairee11is

“In short – they don’t work. Pedestrians often seem oblivious to them, so it inevitably leads to conflict. Dogs are worst as they veer off quickly/unexpectedly. Usually if someone’s dog strays into the path of a bicycle on the cycle part of a shared path it isn’t the dog they blame” @bradley_steve

“Bikes are almost silent & pedestrians have a lifetime of training that footpaths are their safe space. Forcing the bike to be the vehicle in an area where pedestrians believe they’re safe from vehicles just makes that area dangerous to everyone: walkers, riders, pets, etc…” @blacktelescope

“Not in any of the places mentioned but I find Lisburn knockmore road more dangerous on the cycle lane than the road, as you are in conflict with traffic at every junction.” @DieEasySteve

Twitter thread on Belfast:

Need your honest opinions of urban shared footways in your area – what's your experience of walking, wheeling and cycling on them? Here's some examples from across Belfast: pic.twitter.com/sGp9DPTAGb

— NI Greenways (@nigreenways) April 26, 2021

Twitter thread on other areas:

Need your honest opinions of shared footways in your area – what's your experience of walking, wheeling and cycling on them? pic.twitter.com/UMNmRaOvf9

— NI Greenways (@nigreenways) April 25, 2021

Read and download the one page summary Google Data Studio report: Shared past, shared present.. shared future?

[…] As usual, the levels of cycling have flatlined against the three measures in the Bicycle Strategy. This is no shock given there has been virtually no cycle route development in the last five years. […]

[…] Roads Northern Division are the most hardened purists when it comes to shared footway cyclewashing, reporting that 100% of their cycle route projects in the last five years were shared footways. This is despite clear operational guidance not to deploy shared use schemes in urban settings. By […]