In the last of four articles exploring the Department for Infrastructure’s (DfI) review of the Alfred Street cycleway, Bikefast finds itself at the end of the road and the only option is to go back to the beginning.

The first article took a detailed look at the rushed implementation – understandable in the context of the time and with DfI’s heart undeniably in the right place – but with obvious flaws that have been left to fester for too long. The second article laid out the simple fixes which, for some reason, haven’t had either the attention or priority that the negative outcomes warrant – that included a bicycle user hospitalised on the same morning as it was published. And the third article dealt with the spanner in the works of a new cycleway on an adjacent street, which through dissection of the implications and thinking behind the scheme, isolated the underlying issue which protected cycling space on these streets can never fix in isolation – rampant traffic.

Bluntly, Alfred Street was the right street at the right time given a wholly inappropriate intervention. Contrast with Belfast’s Middlepath Street, where volume and speed of vehicular traffic demands physically separated cycling space. Quiet access streets do not.

A place-and conditions-appropriate cycleway on Belfast’s Middlepath Street

Our aim in securing this review was never actually to tinker at the edges of a flawed design, it was to provoke major change to the thinking and scheme control within DfI. They can continue to ignore international lessons on street functionality and plough ahead with this type of cycleway design, or they can take the braver step to deliver interventions which can produce better outcomes for pedestrians and bicycle users.

Welcome to Alfredstraat.

How to turn Alfred Street into a bicycle street

“There’s bigger fish to fry on [Alfred Street] – removal of large amounts of on-street parking, cellularisation of the streets / pedestrianisation of the side streets, 20mph, resident parking schemes etc etc – if DRD/DSD can get a masterplan going to remove bulk of traffic from the Linen Quarter, separated cycling is no longer necessary.”

That was an excerpt of an email I sent exactly five years ago, predating the DfI Walking and Cycling Unit and any hint of a plan to create the Alfred Street cycleway.

The city streets here were choked with vehicles – parking, circulating for parking, travelling through, dropping off and so on – and that was despite the existing kerb protected cycle lane on Upper Arthur Street, the famous Bin Lane.

Constant traffic on the old Bin Lane, the same (if not worse) today

Most importantly they were tight, city centre streets with shops, offices and constant flows of street-level life. Encouraging more of that through enhancing pedestrian space must always be an overriding goal in cities, and the Department for Communities’ (DfC) Streets Ahead projects have been aimed at this. Getting DfI to enable more cycling journeys to the city core with safe space for cycling was another key element of rebalancing urban transport.

But the equivalent streets I’d walked through in Dutch cities didn’t have protected cycleways. They controlled traffic by stopping up streets, creating one-way systems, restricting access to permitted vehicles – leaving streets where people could walk or cycle along the full width most of the time, and vehicles were seen as, and obliged to behave as, tolerated guests.

Putting a cycleway on Alfred Street while maintaining equivalent access for vehicles didn’t feel right. It was fudging a bigger issue.

It was clear what the area needed, and I returned time and again to that word in the email – cellularisation – and everything that could flow from such a simple idea.

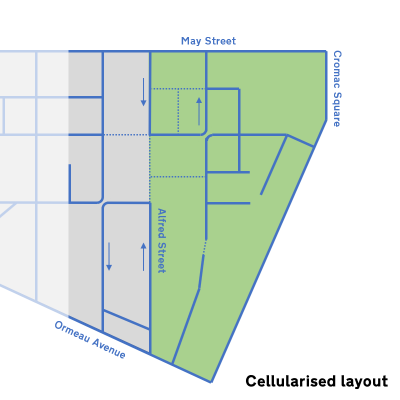

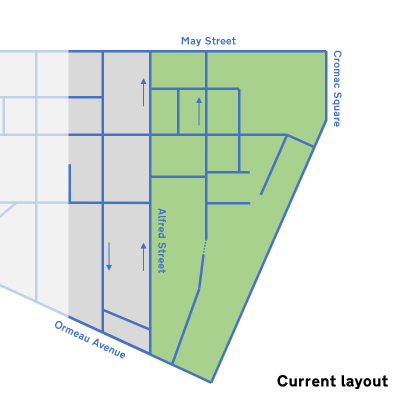

Cellularisation

This was a term introduced to me by (irony alert) DfI. The one member of staff specialising in cycling measures before the advent of the Walking and Cycling Unit had talked to me of restricting traffic within the Linen Quarter this way.

The concept is simple – dividing up the street grid to ensure that whatever way a vehicle enters the area, it has to go back out in the same direction. It retains vehicle access, but access which is only of use to those who need it – not through travel, or being there through the sheer convenience of a fully permeable city quarter to drive around at will.

In the years since, the DfI Walking and Cycling Unit have talked about the same framework – so this is not a Bikefast plan, it’s a Dfi plan – and the right one for these types of streets.

As an aside, this also shows that those tasked with delivering active travel scheme actually do know their stuff. The DfI Walking and Cycling Unit live and breathe that work, are exposed to international best practice, have travelled to Copenhagen and Malmö, have made trips to the Netherlands, have sat with Jan Gehl, have hosted conferences in Belfast headlined by Klaus Bondam. The problem, as evidenced by the sabotaged roll-out of the Alfred Street scheme, there’s a bureaucracy above them which doesn’t allow the right plans to see the light of day.

Cellularisation is a bit of an abstract term, but it’s better known elsewhere by other names, such as the superblocks concept in Barcelona.

Applied to the Linen Quarter as a whole, it would mean vehicles wishing to travel through are kept to the perimeter – on the three ‘Inner Ring’ roads of Great Victoria Street to the west, Ormeau Avenue to the south, Cromac Street to the east, and the city centre spine of May Street to the north.

The example Bikefast proposes below has a simple but revolutionary benefit – physically dividing the Market Community side from the Linen Quarter side for the purposes of vehicle movement. East – west journeys of the type which create dangerous crossings on the current Alfred Street cycleway aren’t possible, while May Street no longer subcontracts almost 50% of its traffic capacity to residential Hamilton Street.

The surface car park at the back of BT’s Telephone House retains its access onto Hamilton Street, with just over 100 spaces and movements through the day. Apart from this, only residents will be able to access these streets.

Quieter for residents, less fumes, better for pedestrians and cyclists accessing the city core. Job done. That proposed cycleway isn’t needed – in fact, no work would be required on Hamilton Street, other than the a physical division of the Joy Street junction and a “No through road for vehicles” sign at the Cromac Square entrance.

The problem is not the road design beyond this point, it’s that traffic can permeate behind this point

North – south through journeys along Alfred Street and Adelaide Street are also no longer possible.

Vehicles accessing Joy Street, Sussex Place and Alfred Street from the May Street side must loop back out to May Street. Daily vehicles movements (Harvester House car park, Northern Ireland Housing Executive loading yard, apartments, houses and small businesses) would be in the low hundreds at most. The Joy Street / Hamilton Street junction would be split in half, serving different vehicle journey types.

Vehicles accessing Alfred Street, Clarence Street and Adelaide Street from the Ormeau Avenue side also must loop back out to Ormeau Avenue. Daily vehicle movements (car parks at Adelaide Exchange car park, St Malachy’s Church, DfI’s Clarence Court, Margharita Plaza

32 – 38 Linenhall Street, 40 Linenhall Street, taxis for the Premier Inn, restaurants and offices) would be in the mid hundreds. The inevitable reduction of spaces and eventual closing of DfI’s private 265 space Clarence Court car park will cut that drastically. The Clarence Street / Adelaide Street junction is also split in half.

At a stroke, through traffic has gone. That’s critical to the second half of the plan.

Fietsstraat

A fietsstraat translates from Dutch simply into “bicycle street”. Again, you might think this is an alien concept being foisted upon DfI, but let’s look again at the press release which announced the new cycleways which included Alfred Street:

“They are continuous routes including measures such as protected two way cycle tracks, bicycle signals and a bicycle friendly street. [Notes: A bicycle street is considered to be a route that is a main route for cycling but only a minor route for motor traffic.]”

Department of Infrastructure press release, 21 Jan 2016

Cycling crossing towards College Street with hard bollards to stop through traffic

The “bicycle street” referenced is actually College Street, a short street on the west end of Belfast city centre, closed on one side to prevent through traffic and to promote the use of the cycleway between West Belfast and the city core.

The basic definition of a bicycle street is where the street is a main route for bicycles and a minor route for vehicles.

Fietsstraat, a bicycle street. High cycling levels and no through traffic. Thx @JSColbeck for wonderful photo. pic.twitter.com/79LYUTBKXC

— CycleSheffield (@CycleSheffield) December 13, 2015

There is no set design parameters for a bicycle street, but the most important aspects to successful implementation are higher cycling levels than vehicle movements, severely reduced speed limits for vehicles, routes that are designed to look more like cycling infrastructure than a road – this article from Mark Wagenbuur at Bicycle Dutch gives an excellent overview.

Fietsstraat in Delft where bikes rule and traffic is restricted. Something like this for the Viaduct after Skypath opens please. pic.twitter.com/WvlTpC3XU9

— Kent Lundberg (@kentslundberg) July 2, 2017

Vehicles are not banned from bicycle streets, but through route unravelling and keeping A-B vehicle movements to the perimeter of an area, while bicycles and pedestrians permeate at will, creates the right conditions – just as with our cellularisation plan. And that’s critical:

“The CROW recommendation is very clear. There should at least be double the number of people cycling than there are motor vehicles. So the ratio between cycling and motor traffic should be 1 motor vehicle to 2 people cycling, or preferably 1 motor vehicle to 4 people cycling or even more.”

Another new bicycle street in Utrecht (Bicycle Dutch)

By removing through traffic from Alfred Street we drastically reduce the number of vehicle movements on the street, and what’s left is mostly during weekday rush hours. Remove all but a few essential on-street parking bays – leaving disabled bays exclusively – and circulating traffic goes too.

DfI have already indicated that along Alfred Street (presumably not counting the crossing traffic which fouls Franklin Street and Hamilton Street) bicycle traffic is currently at parity with vehicle traffic.

Andrew Grieve @deptinfra points to Belfast's Alfred Street where cycling traffic now at parity with vehicle traffic, due to the protected cycleway #wow #bikelife2017 pic.twitter.com/WrmxSAOAdA

— NI Greenways (@nigreenways) November 14, 2017

Eliminate through traffic in the bicycle street set-up, and cycling would be the dominant mode.

What would a bicycle street look like?

Let’s take those location specific designs which we drew up in articles one and two and apply the bicycle street design under a ‘one-way for vehicles, two-way for bicycles’ framework.

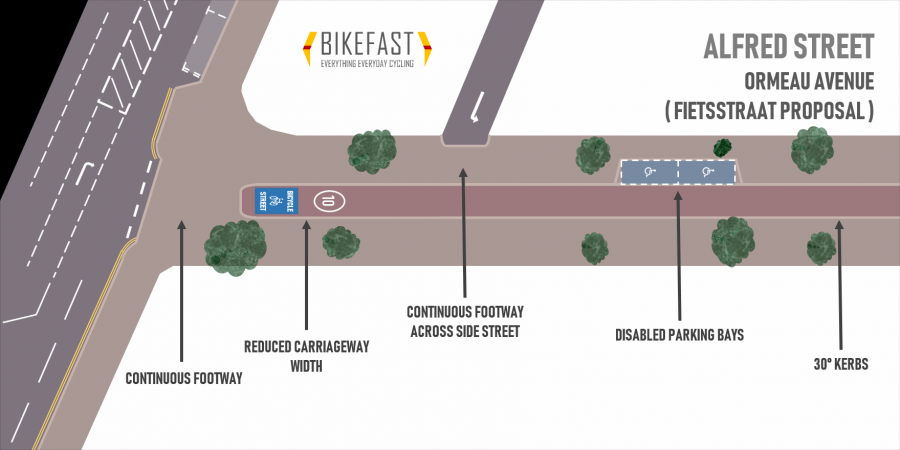

Ormeau Avenue

Missing from the simple fixes suggestion but implemented here is the upgrade to a fully continuous footway along Ormeau Avenue. Taking the proper Dutch design principles to make the remaining drivers cautiously cross the footway will provide a necessary check on speed.

Entering the street there’ll immediately be a 10mph limit sign to further indicate that this is a different type of street. Implementing road surface logo ideas from the Netherlands, a ‘bicycle street’ sign can convey priority for vulnerable users.

On street parking is removed, save for a few designated areas specifically for those in greatest need ie disabled blue badge holders. This also drastically simplifies and cuts the parking enforcement required on the street.

Bicycle street designs vary and offer different operational realities, however a tight ‘carriageway’ would further help to reduce speed through design, and the possible use of 30 degree kerbs could enable bicycle users to move to and from the carriageway as needed.

By taking the carriageway width down to a minimum, the footways on both sides of the street can be generously extended – opening up possibilities for innovative use as we’ll see later.

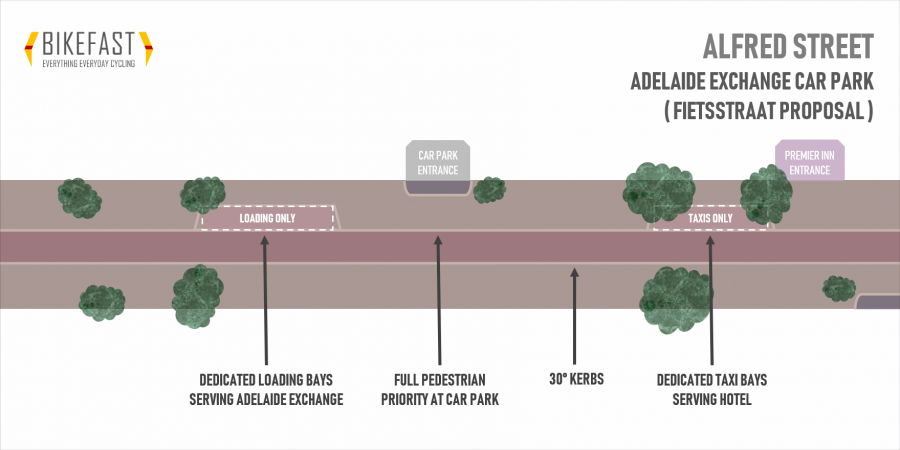

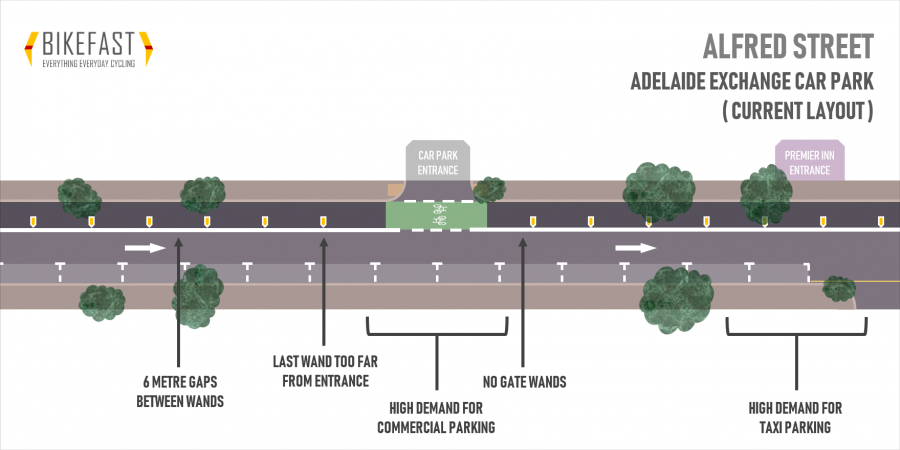

Adelaide Exchange car park

Designated loading bays sit near the Adelaide Exchange entrance to facilitate regular waste collection and loading operations. With greatly extended footways replacing the current cycleway and on-street parking, there is plenty of space to cope with instances of excess demand for loading / unloading space.

One of the major problems & easy fixes if (big if) @deptinfra decide to retain this current set-up on Alfred St – here's DB Schenker doing the right thing (not blocking the cycleway) but without dedicated loading bays (where the skip is), other drivers make the cycleway lethal. pic.twitter.com/5YnZMQBQum

— NI Greenways (@nigreenways) December 6, 2018

Give the whole street a 10 minute loading window and vehicles can sit off the carriageway for short periods to go about essential business.

A dedicated taxi area beside the Premier Inn to meet demand through the day and especially in the evenings.

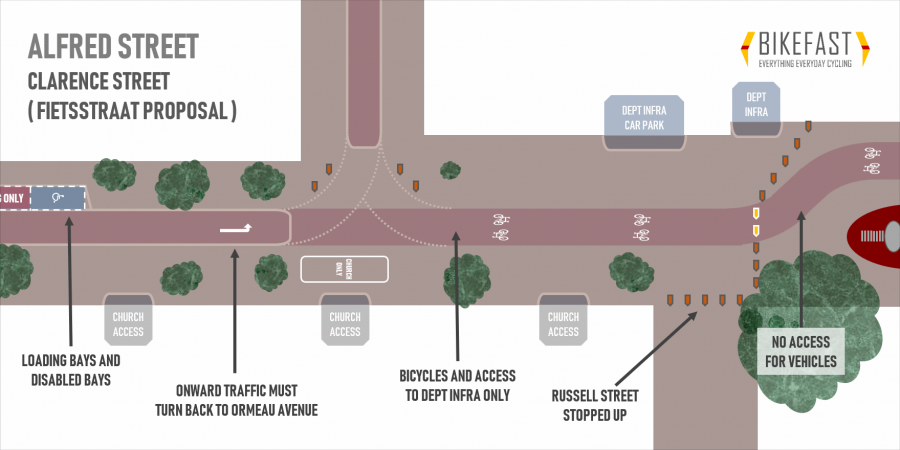

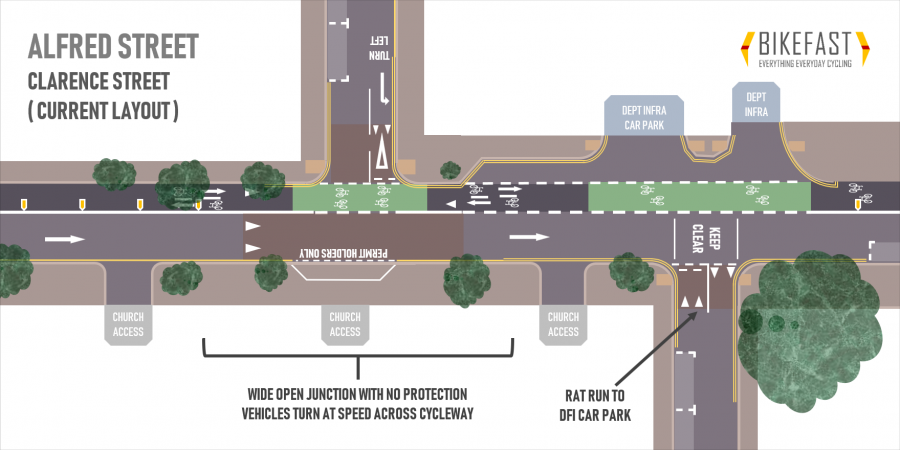

Clarence Street

The cellularisation comes into play as any vehicles which have entered at Ormeau Avenue must now turn back towards Ormeau Avenue. One option is to remove the carriageway markings through the turn, offering priority to pedestrians and bicycle users crossing here.

Russell Street is stopped up permanently and the top end could be a good place to relocate the Alfred Street Belfast Bikes Station.

Vehicles can continue straight to reach the Clarence Court car park entrance and the loading entrance, and this space can double as a turning circle for larger servicing vehicles accessing this building.

Beyond this, permanent barriers would be placed to prevent vehicles travelling beyond and a dedicated bicycle path would be used to keep bicycle users in an orderly flow – especially for the benefit of visually impaired pedestrians who need clarity, not shared space.

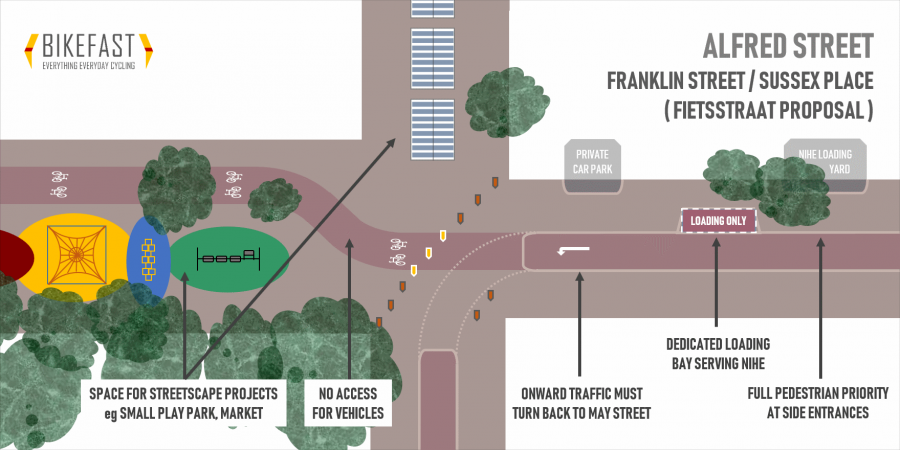

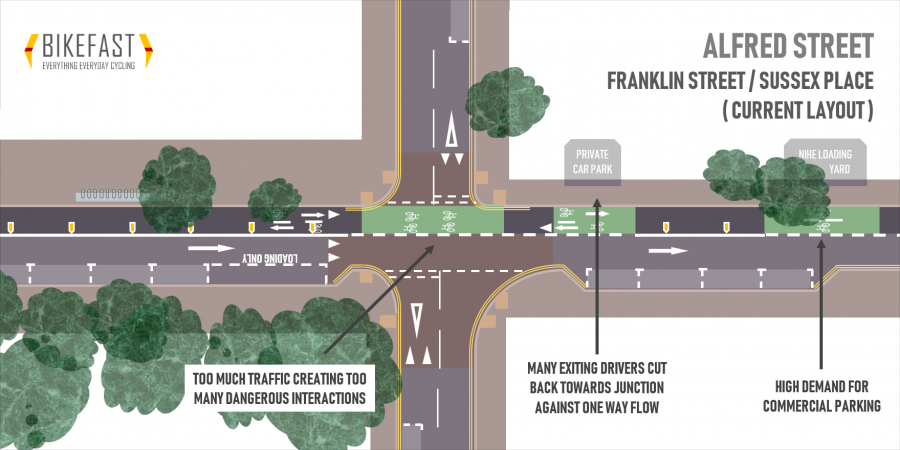

Franklin Street / Sussex Place

The space between vehicle barriers is where things get interesting, and where better than at the back of DfI’s headquarters?

By creating vehicle-free pockets we give the city options to get creative. Permanent benches and tables could promote dwell and possible boost catering businesses in the area. Defined market stall space could encourage small start-ups to trade in a new pedestrian / entrepreneurial arc between the city core and St George’s Market.

Or something really radical – using the space behind Clarence Court for a pocket playground. Adding this would serve both the Linen-side Market Community and the growing apartment-based community in the wider Linen Quarter who lack green space and play space.

New 'Pocket park'! Brokkys Crofte community playground event at @LFArchitecture. @MaxDewdney @PhinHarper https://t.co/4jZuHKbmUQ #LFA2017 pic.twitter.com/GrCfHYWV6q

— Heyne Tillett Steel (@HTS_London) June 27, 2017

Or a pocket community garden, which have grown in popularity around Belfast in recent years.

Community garden at Avoniel flourishing – the green grassy slopes of Ballymacarrett pic.twitter.com/2u9KVrc0y3

— john kyle (@cllrjohnkyle) July 11, 2013

Indeed only this week the Linen Quarter Business Improvement District team tweeted out exactly this type of idea.

We also want to work with @GroundworkNI to develop a new community garden for the Linen Quarter. We will be donating £250 towards this for every local business that signs up to our new waste management service. Come along on 22 Jan to find out more. https://t.co/HGNiqynIju

— Linen Quarter BID (@LinenQuarterBID) January 2, 2019

When even the High Line in New York can find the space for wonderful wildflower patches, we have more space than you think to do something spectacular on Alfred Street.

The second part of the cellularisation plan sees traffic circulating around Alfred Street, Sussex Place and Joy Street coming in from May Street and going back out again. On-street parking is kept to the absolute minimum with loading areas to service NIHE and Harvester House.

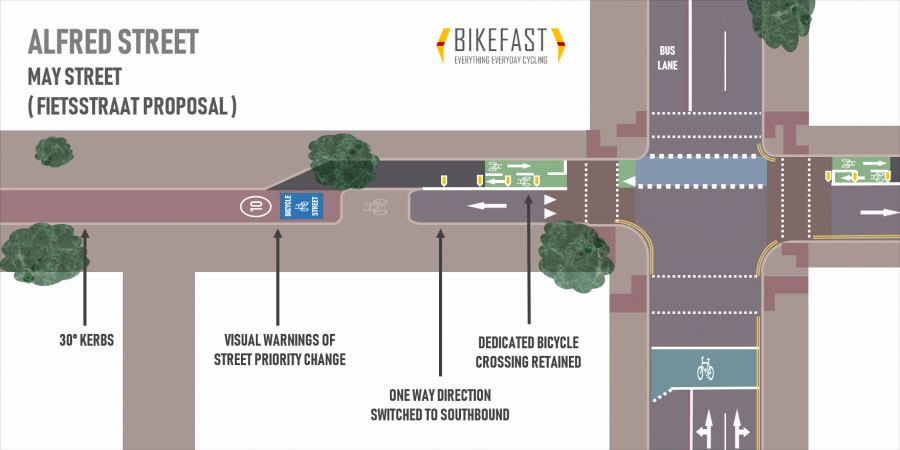

May Street

This is the one major change of traffic direction which both enables the cellularisation plan to be delivered, and solves the ongoing problem of unlawful left turns out of May Street. The traffic direction is reversed, with vehicles entering left from May Street onto Alfred Street, before being turned back out again via Joy Street.

To support this, the dedicated bicycle crossing on May Street is retained, so there is a need for a transition point. Merging conflicts here would be minimal as bicycle traffic crossing south from Upper Arthur Street will always be on a separate phase to vehicles turning in from May Street.

Upper Arthur Street

We come full circle, to the point I drove home when first presented with the Alfred Street cycleway plans. This was the street that I insisted should have through traffic removed to better support street level life, business activities and active travel movements.

And yet, with Alfred Street offering a better opportunity to trial these concepts because of the need to improve safety, it makes sense to retain Upper Arthur Street’s layout for now. Give Alfred Street’s fietsstraat layout and cellularisation reforms a year to bed in and demonstrate their worth before tackling the Bin Lane.

Here's Belfast's #BinLane (Upper Arthur St) with vehicle traffic removed.. "@AKLdesignchamp: Cool street in Auckland pic.twitter.com/buEdLTHoT6"

— NI Greenways (@nigreenways) March 23, 2015

Not only would there be benefits for the independent businesses in terms of more footfall and possible outdoor extensions (food establishments especially) but something else remarkable for our city.

Once the Gasworks Bridge is built, and the Alfredstraat concept is delivered, it would create a pedestrian and bicycle priority route from High Street to the southern tip of Ormeau Park, fully 3km long.

Now that’s a liveable city idea worth fighting for.

Summary

Over the last six and a half years of writing about cycling issues, there have been times when I knew I was introducing concepts that were too alien or too abstract for DfI to consider implementing.

This article is about trialling a fietsstraat on a Belfast city centre street, and this time it’s not pie in the sky – in fact, it chimes perfectly with existing plans, strategies and real world developments.

Take 2016’s Linen Quarter Masterplan, developed for Belfast City Council by Planit Intelligent Environments.

Clarence Street indicative illustration (St Malachy’s Church in the background) © Belfast City Council / Planit

Not a kick in the backside away from our fietsstraat layout. Read the blurb:

“Rebalancing the street network is critical to make a more attractive and vibrant Quarter, while at the same time retaining essential vehicle movement and servicing.

The design of the street network should respond to key pedestrian routes, offering greater opportunity for businesses to spill out onto the street and add to street life.

The street hierarchy within the Quarter should be reflected in the street design, pavement width and crossing detail. Extended pavements, with a clear zone for street furniture or car parking offer greater space for pedestrians and help to emphasise movement.

The extra space also offers opportunity for tree planting, helping to emphasise and frame long views and vistas.

Pavement width should extend out to ‘pinch the street’ and provide opportunities for seating in defined zones away from main circulation route while retaining appropriate street width for vehicle movement.“

Where that masterplan went wrong was presenting attractive ‘after’ street visualisations and paving upgrades which showed a lack of vehicles. Without managing demand and access, those ‘after’ streets will still be full of circulating and travelling traffic at all times of the day.

Talk of “vehicular priority streets” and ”‘Flow’ to be encouraged on busy north – south streets” ignored the elephant in the room and left this area of Belfast out of step with global trends towards city centre traffic removal.

DfI has to demonstrate the fearlessness to take the Linen Quarter Masterplan and apply the necessary traffic removal measures which it desperately needs. Or maybe Planit can revise that aspect in this timely review.

We've asked @PlanitIE to refresh vision for Linen Quarter & Shaftesbury to help land £1 billion already anticipated (2016-26) and keep promoting for investment @Translink_NI @BBCnireland @HastingsHotels @AndrasHouse @McAleerRushe @belfastcc @deptinfra @CommunitiesNI @BelfastMIPIM pic.twitter.com/594zxVH6c6

— Linen Quarter BID (@LinenQuarterBID) January 3, 2019

Across the other side of the Linen Quarter, the bungled Better Bedford Street project (more on that failure another time) had one redeeming feature – the willingness for DfI to coordinate with other departments and stakeholders to quickly deliver trial interventions with the intent (if not the outcome in this case) of improving streets for people, not vehicles.

Hats off to @deptinfra @CommunitiesNI @belfastcc & friends for starting to pilot street animation at #BetterBedfordStreet. Harder than it looks, but a positive new way of working for NI. Key to now try/learn/adapt&apply. #tacticalurbanism #LivingPlacesNI pic.twitter.com/VTJVZ9T3QY

— James Hennessey (@JamesEHennessey) September 19, 2018

Better Bedford Street itself is seen as a testing ground for the next phase of DfC’s Streets Ahead project, again aimed at better place making and pedestrian experience in the city centre. Shamefully, every previous phase of Streets Ahead studiously ignored any idea of integrating dedicated cycling space, which leaves a massive barrier for northward bicycle journeys through Belfast.

DfC’s one-way Streets Ahead design for Donegall Place didn’t reckon on anyone cycling northbound in Belfast

But again, there is the budget, priority and will to work to make streets better for the most important users – people, not vehicles.

And the massive response to the Bank Buildings fire in the centre of Belfast showed something amazing. Even in adversity, and with streets closed off to pedestrian footfall and all vehicle traffic for months, Christmas shopping footfall went up. This was due in no small part to the marketing efforts and promotional public transport fares, but the re-purposing of the main shopping street space towards parklets, laying of artificial turf, seating, small business, children’s play activities, had a massive impact on how people saw and used their city centre.

A new vision for street use in Belfast, or a short breath before being swamped by vehicles again?

The point is, all of these converging visions for a different way of treating and designing our inner city streets already exist in government circles. They are threads which could be woven together into better projects, producing great outcomes, and putting people before vehicles.

It needs someone to tie those threads together.

That’s how the DfI Walking and Cycling Unit was sold to us all – a team who could work to coordinate across government departments to deliver the cross-cutting outcomes which active travel delivers in spades – health, congestion, tourism, liveable cities, independence. We’ve seen that work at its best with the Public Health Agency able to fund the latest round DfI’s greenway strategy.

But the hardest silos to crack are usually within, and I think that’s why DfI isn’t able to truly tackle vehicle dominance head-on. To deliver a fietsstraat vision for a street or city quarter, it comes into contact with other DfI silos with more clout and conflicting aims to keep traffic progressing.

Alfred Street designed the right way could be something of template for other streets, routes and areas. But like the failed cycleway design, the goal isn’t to have a prescriptive set of interventions which we force into places which might not need them. It’s about freeing DfI, the Walking and Cycling Unit and senior management, to think on their feet, create place-appropriate schemes, and begin to align with the global moves towards strategic restriction and removal of traffic from city centres.

Norway is banning cars from the centre of Oslo.

Parking spaces are to be replaced with flower beds. 🌸

60km of cycle lanes are being built. 🚲We have solutions to the #climate crisis. Let's implement them. #energy #sustainability #innovation #greencities #climatechange pic.twitter.com/ddG8U3xLuo

— Mike Hudema (@MikeHudema) January 7, 2019

The Alfred Street cycleway was only ever a pilot project. It’s worked to a certain extent, but it’s reached its limit of usefulness. Turning it into a bicycle street off the back of a wider strategic move to limit vehicles within the Linen Quarter through cellularisation is what it desperately needs now.

The Department is seeking your views on “what improvements can be made to the operation of Alfred Street and Upper Arthur Street in line with the draft Programme for Government”.

Send your views on the Department for Infrastructure’s Alfred Street cycleway review here.

Alfred Street review articles

Alfred Street cycleway review – the issues

How to fix the Alfred Street cycleway

Extending a cycleway along Hamilton Street?

That’s a powerful piece. Cogent and well argued. I hope it gets an appropriately receptive by DFI and BCC.

The ink is barely dry and Sustrans and DfI cycling unit people were out on the corner of Alfredstraat and Ormeau Avenue discussing the options. I briefly explained my views, to which they all nodded and went “I know, I know”.

[…] Alfredstraat – from cycleway to bicycle street […]

[…] The term has been used to describe work to reduce traffic levels within areas of Barcelona, and Bikefast has proposed a superblock-style approach to re-configuring Belfast’s Linen Quarter. […]